| |

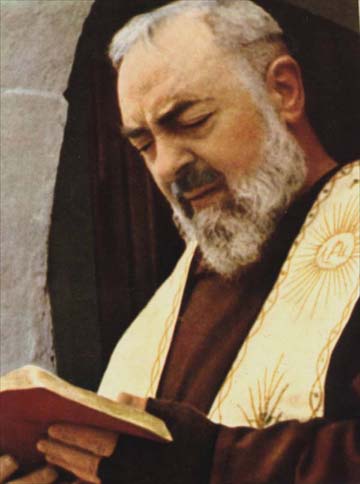

Padre Pio

Foundation

This site is dedicated to the life and work of Padre Pio.

|

|

|

Padre Pio

Padre Pio is now Saint Padre Pio. Padre Pio was canonized by Pope John Paul II

on June 16, 2002. For many years in the past, thousands of people have

climbed up the mountain path in San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy, to visit

the

great Padre Pio,

or at least see Padre Pio, the famous stigmatized Capuchin monk. Padre

Pio was the first priest in the history of the Catholic Church to bear

the holy wounds of Jesus Christ.

Padre Pio was born in the village of Pietrelcina, Italy, on May 25,

1887. Padre Pio's parents gave him the name of Francesco Forgione. There

were eight children in total, three of whom died in infancy. Padre Pio's

parents were simple hard working farmers. They were so poor, that Padre

Pio's

father Orazio went to the United States twice, in order to be able to

provide for his family and earn enough money to educate Padre Pio for

the priesthood.

As a child, Padre Pio avoided the company of other children, and did not

take part in their games. Padre Pio had a great horror of sin and cried

when he heard anyone blaspheming, or taking God’s name in vain. Even

when Padre Pio was seven years old, Padre Pio could tell if somebody was in the

state of sin. From the time Padre Pio was a child, Padre Pio would often think

about the things of God and keep himself recollected.

|

Please help

the Padre Pio Foundation in this world

of pain and hunger Please donate, all donations are tax deductible. Thank you.

|

Padre Pio: Wonderworker or Charlatan?

Of the twentieth century’s two most famous stigmatics (those who

experience the supposedly supernatural wounds of Jesus), both Therese

Neumann and Padre Pio were suspected of fraud, but Pio went on to

sainthood and was canonized in 2002. In April 2008 his body was

exhumed and put on display in a church crypt in San Giovanni Rotondo,

Italy, a move that both attracted throngs of the credulous and

provoked outrage among some Pio devotees. It also renewed questions

about the genuineness of the stigmata and other phenomena associated

with Pio.

A Capuchin Friar

Born Francesco Forgione on May 25, 1887, in the town of Pietrelcina,

Pio grew up surrounded by superstitious beliefs and practices. His

mother took him soon after birth to a fortuneteller to have his

horoscope cast and at the age of two to a witch who attempted to cure

an intestinal disorder by holding him upside down and chanting spells.

As a boy he was tormented by nighttime “monsters,” and he conversed

with Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and his guardian angel. He also had other

mystical experiences (Ruffin 1982, 21–23, 79) that today are

associated with a fantasy-prone personality.1

He was “frequently ill and emotionally disturbed” and claimed he was

often physically attacked by evil spirits (Wilson 1988, 88, 144).

In 1903, he entered The Order of Friars Minor, Capuchin—a

conservative Catholic order that traces its origin to St. Francis of

Assisi (1182–1226), the first stigmatic. The new initiate was called

Fra (“Brother”) Pio (“Pious”), after the

sixteenth-century pope, St. Pius V (Ruffin 1982, 35, 39). Pio

continued to hear voices and experience visions, and in 1910 he began

to experience the stigmata just after being ordained a priest.

As Padre Pio continued to exhibit the phenomenon, he began to

attract a cult following. It was said he could look into people’s

souls and, without them saying a word, know their sins. He could also

allegedly experience “bilocation” (the ability to be in two places at

the same time), emit an “odor of sanctity,” tell the future, and

effect miraculous cures (Wilkinson 2008; Rogo 1982, 98–100). Village

hucksters sold his credulous disciples alleged Pio relics in the form

of swatches of cloth daubed with chicken blood (Ruffin 1982, 153).

The local clergy accused Padre Pio’s friary of putting him on

display in order to make money. They expressed skepticism about his

purported gifts and suggested the stigmata were faked.

The Phenomena

The claims of Padre Pio’s mystical abilities are unproven,

consisting of anecdotal evidence—a major source being the aptly named

Tales of Padre Pio (McCaffery 1978). Pio’s touted psychic

abilities seem no better substantiated than the discredited claims of

the typical fortuneteller or medium (e.g., Nickell 2001, 122–127,

197–199). Many of his “bilocations” are analogous to Elvis Presley

sightings, while some are—at best—consistent with hallucinations (such

as one reported during a migraine attack or others occurring when the

experiencer was near sleep or in some other altered state [McCaffery

1978, 24–36]). The reputed “odor of sanctity,” said Pio’s accusers,

“was the result of self-administered eau-de-cologue” (“Pio”

2008).

As to Pio’s miraculous healings, they— like other such claims (Nickell

2001, 202–205)—are not based on positive evidence of the miraculous.

Instead, the occurrences are merely held to be “medically

inexplicable,” so claimants are engaging in the logical fallacy of

arguing from ignorance (drawing a conclusion based on a lack of

knowledge). Faith-healing claims often have alternative explanations,

including misdiagnosis, psychosomatic conditions, spontaneous

remissions, prior medical treatment, and other effects, including the

body’s own healing ability. Cases are complicated by poor

investigation and even outright hoaxing. One man’s claim of instant

healing of a leg wound by Padre Pio, for example, was bogus; his

doctor attested it “had, in fact, been healed for six months or more”

(Ruffin 1982, 159).

But it is Pio’s stigmata that have made him famous. Unfortunately,

some examining physicians believed his lesions were superficial, but

their inspections were made difficult by Pio’s acting as if the wounds

were exceedingly painful. Also, they were supposedly covered by “thick

crusts” of blood. One distinguished pathologist sent by the Holy See

noted that beyond the scabs was an absence of “any sign of edema, of

penetration, or of redness, even when examined with a good magnifying

glass.” Another concluded that the side “wound” had not penetrated

the skin at all (Ruffin 1982, 147–148). Some thought Pio

inflicted the wounds with acid or kept them open by continually

drenching them in iodine (Ruffin 1982, 149–150; Moore 2007; Wilkinson

2008).

Nevertheless, some of the faithful were so intent on defending Pio

that they made incredible claims. One was the insistence that the hand

lesions, which skeptics thought were superficial injuries, were

through-and-through wounds—“so much so,” insisted Pio’s devoted family

physician, that one could see light through them.” Of course, this is

nonsense in view of authentic wounds in general and Pio’s thickly

blood-crusted ones in particular (Ruffin 1982, 146–147).

There were other problems with the “wounds,” including their

location. Only the gospel of John (19:34) mentions the lance wound in

Jesus’ side, and John fails to specify which side. St. Francis’ was on

the right, whereas Padre Pio’s was on the left. Also, witnesses

described his side wound as in the shape of a cross; in other words,

it had a stylized rather than realistic (lance-produced) form (Ruffin

1982, 145, 147).2

Moreover, his wounds were in the hands rather than the wrists (some

anatomists argue that nailed hands could not support the body of a

crucified person and would tear away). When asked about this, Pio

replied casually, “Oh it would be too much to have them exactly as

they were in the case of Christ” (Ruffin 1982, 145, 150). (One is

reminded of Therese Neumann, whose “nail wounds” shifted from round to

rectangular over time, presumably as she learned the true shape of

Roman nails [Nickell 2001, 278].) Moreover, Padre Pio lacked wounds on

the forehead (as from a crown of thorns [John 19:2]).

For years Pio wore fingerless gloves on his hands, perpetually

concealing his wounds (Ruffin 1982, 148). His supporters regard this

as an act of pious modesty. However, another interpretation is that

the concealment was a shrewd strategy that eliminated the need for him

to maintain his wounds. Before his death, frail, weary, with “rheumy

eyes seemingly fixed on another world,” Padre Pio celebrated Mass.

According to Ruffin (1982, 305), “For the first time in anyone’s

memory, he did not attempt to hide his hands at any point in the

service. To the amazement of everyone there, there was no trace of any

wound.” At his death on September 23, 1968, his skin was unblemished.

So, were Padre Pio’s phenomena genuine? Many other stigmatics—like

Magdalena de la Cruz in 1543—confessed to faking stigmata. Maria de la

Visitacion, the “holy nun of Lisbon,” was caught painting fake wounds

on her hands in 1587. Pope Pius IX himself privately branded as a

fraud Palma Maria Matarelli (1825–1888), insisting that “she has

befooled a whole crowd of pious and credulous souls.” Suspiciously,

under surveillance, Therese Neumann (1898– 1962) produced actual blood

flows only when the phenomenon was “hidden from observation.” And as

recently as 1984, stigmatic Gigliola Giorgini was convicted of fraud

by an Italian court (Wilson 1988, 26–27, 42, 53, 147).

Even a defender of Padre Pio’s stigmata, C. Bernard Ruffin (1982,

145), admits, “For every genuine stigmatic, whether holy or

hysterical, saintly or satanic, there are at least two whose wounds

are self-inflicted.” Catholic scholar Herbert Thurston (1952, 100)

found no acceptable case after St. Francis of Assisi. Thurston

believed the phenomenon was due to suggestion, but Padre Pio himself

responded to such theorizers: “Go out to the fields and look very

closely at a bull. Concentrate on him with all your might. Do this and

see if horns grow on your head!” (qtd. in Ruffin 1982, 150). As for

St. Francis, his extraordinary zeal to imitate Jesus may have led him

to engage in a pious deception (Nickell 2001, 276–283).

Canonization

Not only was Padre Pio accused of inducing his stigmata with acid,

he was also alleged to have misused funds and to have had sex with

female parishioners—in the confessional. The founder of the Catholic

university hospital in Rome branded Pio “an ignorant and

self-mutilating psychopath who exploited people’s credulity” (“Pio”

2008).

The faithful were undeterred, however, and after Pio’s death there

arose a popular movement to make him a saint. Pope John Paul II—whose

papacy sped up the process of canonization and proclaimed more saints

than any other in history (Grossman 2002)—heard the entreaties. Pio

was beatified in 1999. On June 16, 2002, he was canonized as Saint Pio

of Pietrelcina, but not before at least two statues of him wept in

anticipation. Unfortunately, the bloody tears on one turned out to

have been faked (a drug addict used a syringe to apply trickles of his

own blood), and a whitish film on one eye of the other was determined

to have been insect secretion (“Crying” 2002).

Interestingly, neither of the two proclaimed miracles of Pio (one

used for his beatification, the other for canonization) involved

stigmata. Instead, they were healings, assumed miraculous because they

were determined to be medically inexplicable. In short, the Church

never affirmed Pio’s stigmata as miraculous.

Of course, not everyone was happy with the canonization of Pio.

Historian Sergio Luzzatto wrote a critical biography of Pio called

The Other Christ. Luzzatto cited the testimony of a

pharmacist recorded in a document in the Vatican’s archive. Maria De

Viot wrote: “I was an admirer of Padre Pio and I met him for the first

time on 31 July 1919.” She revealed, “Padre Pio called me to him in

complete secrecy and telling me not to tell his fellow brothers, he

gave me personally an empty bottle, and asked if I would act as a

chauffeur to transport it back from Foggia to San Giovanni Rotondo

with four grams of pure carbolic acid” (Moore 2007). But if the acid

was for disinfecting syringes, as Pio had alleged to the pharmacist,

why the secrecy? And why did Pio need non-diluted acid?

Investigation shows the timing of this reported incident is

significant. The previous September, Pio and some of the other friars

at San Giovanni Rotondo were administering injections to boys who were

ill with influenza. Alcohol not being available, an exhausted doctor

left carbolic acid to be used for sterilizing needles and injection

sites, while neglecteing to tell the friars it had to be diluted. As a

result, Pio and another friar were left with “angry red spots” on

their hands. When Pio was subsequently alleged to have exhibited

stigmata, the other friar at first thought the wounds were from the

carbolic acid. Although Pio allegedly exhibited stigmata on his hands

as early as 1910, the “permanent” stigmata appeared, apparently, not

long after the carbolic-acid misuse (Ruffin 1982, 69–71, 138–143).

Sergio Luzzatto drew anger for publicizing the pharmacist’s

testimony. The Catholic Anti-Defamation League accused the historian

of “spreading anti-Catholic libels,” and the League’s president

sniffed, “We would like to remind Mr. Luzzatto that according to

Catholic doctrine, canonisation carries with it papal infallibility”

(Moore 2007).

Exhumation

Forty years after the death of Padre Pio in 1968, his remains were

exhumed from their crypt beneath a church in San Giovanni Rotondo. The

intention of church officials was to renew reverence and so boost a

flagging economy. Padre Pio, explained the Los Angeles Times,

is “big business” (Wilkinson 2008).

No doubt many anticipated that the saint’s body would be found

incorrupt. The superstitious believe that the absence of decay in a

corpse is miraculous and a sign of sanctity (Cruz 1977). In fact,

under favorable conditions even an unembalmed body can become

mummified. Dessication may result from interment in a dry tomb or

catycomb. Conversely, perpetually wet conditions may cause the body’s

fat to form a soaplike substance known as “grave wax”; subsequently,

the body may take on the leathery effect of mummification (Nickell

2001, 49).

Alas, Pio’s body, despite embalment (by injections of formalin),

was only in “fair condition.” So that it could be displayed, a London

wax museum was commissioned to fashion a lifelike silicon mask of Pio,

complete with his full beard and bushy eyebrows. The “cosmetically

enhanced corpse” went on display April 24, 2008, in a glass-and-marble

coffin (where it is to repose until the end of September 2009) “amid

weeping devotees and eager souvenir-hawkers” (Wilkinson 2008; “Pio”

2008). For those who wonder: no, there is no visible trace of

stigmata.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Herb Schapiro, who continues to send me useful

news clippings, and Tim Binga, director of CFI Libraries, for his

continued research assistance.

Notes

- For a discussion of fantasy proneness, see Nickell 2001, 84–85,

298–299.

- The three-inch side wound was seen relatively rarely and,

although “most witnesses” said it was cruciform, others described it

as being “a clean cut parallel to the ribs” (Ruffin 1982, 147).

After his death in 1968, Padre Pio's body was placed

to rest In the crypt of the Sanctuary of St. Mary of Graces.

The body was exhumed in 2008, and displayed for the

veneration of the faithful until 2009.

In 2010 the body was transferred in the new San Pio

church, and placed to rest in the golden crypt.

Padre Pio was declared Blessed in 1999, and Saint in

2002

First Resting Place

Padre Pio's body was placed in the crypt of Saint Mary

of Graces.

He had expressed a whish that couldn't be fulfilled:

"When I die I wish to be buried underground, because

I am a worm, a great sinner."

Pope John Paul II visited Padre Pio's grave on May

27, 1987

Padre Pio: Wonderworker or Charlatan?

Of the twentieth century’s two most famous stigmatics (those who

experience the supposedly supernatural wounds of Jesus), both Therese

Neumann and Padre Pio were suspected of fraud, but Pio went on to

sainthood and was canonized in 2002. In April 2008 his body was

exhumed and put on display in a church crypt in San Giovanni Rotondo,

Italy, a move that both attracted throngs of the credulous and

provoked outrage among some Pio devotees. It also renewed questions

about the genuineness of the stigmata and other phenomena associated

with Pio.

A Capuchin Friar

Born Francesco Forgione on May 25, 1887, in the town of Pietrelcina,

Pio grew up surrounded by superstitious beliefs and practices. His

mother took him soon after birth to a fortuneteller to have his

horoscope cast and at the age of two to a witch who attempted to cure

an intestinal disorder by holding him upside down and chanting spells.

As a boy he was tormented by nighttime “monsters,” and he conversed

with Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and his guardian angel. He also had other

mystical experiences (Ruffin 1982, 21–23, 79) that today are

associated with a fantasy-prone personality.1

He was “frequently ill and emotionally disturbed” and claimed he was

often physically attacked by evil spirits (Wilson 1988, 88, 144).

In 1903, he entered The Order of Friars Minor, Capuchin—a

conservative Catholic order that traces its origin to St. Francis of

Assisi (1182–1226), the first stigmatic. The new initiate was called

Fra (“Brother”) Pio (“Pious”), after the

sixteenth-century pope, St. Pius V (Ruffin 1982, 35, 39). Pio

continued to hear voices and experience visions, and in 1910 he began

to experience the stigmata just after being ordained a priest.

As Padre Pio continued to exhibit the phenomenon, he began to

attract a cult following. It was said he could look into people’s

souls and, without them saying a word, know their sins. He could also

allegedly experience “bilocation” (the ability to be in two places at

the same time), emit an “odor of sanctity,” tell the future, and

effect miraculous cures (Wilkinson 2008; Rogo 1982, 98–100). Village

hucksters sold his credulous disciples alleged Pio relics in the form

of swatches of cloth daubed with chicken blood (Ruffin 1982, 153).

The local clergy accused Padre Pio’s friary of putting him on

display in order to make money. They expressed skepticism about his

purported gifts and suggested the stigmata were faked.

The Phenomena

The claims of Padre Pio’s mystical abilities are unproven,

consisting of anecdotal evidence—a major source being the aptly named

Tales of Padre Pio (McCaffery 1978). Pio’s touted psychic

abilities seem no better substantiated than the discredited claims of

the typical fortuneteller or medium (e.g., Nickell 2001, 122–127,

197–199). Many of his “bilocations” are analogous to Elvis Presley

sightings, while some are—at best—consistent with hallucinations (such

as one reported during a migraine attack or others occurring when the

experiencer was near sleep or in some other altered state [McCaffery

1978, 24–36]). The reputed “odor of sanctity,” said Pio’s accusers,

“was the result of self-administered eau-de-cologue” (“Pio”

2008).

As to Pio’s miraculous healings, they— like other such claims (Nickell

2001, 202–205)—are not based on positive evidence of the miraculous.

Instead, the occurrences are merely held to be “medically

inexplicable,” so claimants are engaging in the logical fallacy of

arguing from ignorance (drawing a conclusion based on a lack of

knowledge). Faith-healing claims often have alternative explanations,

including misdiagnosis, psychosomatic conditions, spontaneous

remissions, prior medical treatment, and other effects, including the

body’s own healing ability. Cases are complicated by poor

investigation and even outright hoaxing. One man’s claim of instant

healing of a leg wound by Padre Pio, for example, was bogus; his

doctor attested it “had, in fact, been healed for six months or more”

(Ruffin 1982, 159).

But it is Pio’s stigmata that have made him famous. Unfortunately,

some examining physicians believed his lesions were superficial, but

their inspections were made difficult by Pio’s acting as if the wounds

were exceedingly painful. Also, they were supposedly covered by “thick

crusts” of blood. One distinguished pathologist sent by the Holy See

noted that beyond the scabs was an absence of “any sign of edema, of

penetration, or of redness, even when examined with a good magnifying

glass.” Another concluded that the side “wound” had not penetrated

the skin at all (Ruffin 1982, 147–148). Some thought Pio

inflicted the wounds with acid or kept them open by continually

drenching them in iodine (Ruffin 1982, 149–150; Moore 2007; Wilkinson

2008).

Nevertheless, some of the faithful were so intent on defending Pio

that they made incredible claims. One was the insistence that the hand

lesions, which skeptics thought were superficial injuries, were

through-and-through wounds—“so much so,” insisted Pio’s devoted family

physician, that one could see light through them.” Of course, this is

nonsense in view of authentic wounds in general and Pio’s thickly

blood-crusted ones in particular (Ruffin 1982, 146–147).

There were other problems with the “wounds,” including their

location. Only the gospel of John (19:34) mentions the lance wound in

Jesus’ side, and John fails to specify which side. St. Francis’ was on

the right, whereas Padre Pio’s was on the left. Also, witnesses

described his side wound as in the shape of a cross; in other words,

it had a stylized rather than realistic (lance-produced) form (Ruffin

1982, 145, 147).2

Moreover, his wounds were in the hands rather than the wrists (some

anatomists argue that nailed hands could not support the body of a

crucified person and would tear away). When asked about this, Pio

replied casually, “Oh it would be too much to have them exactly as

they were in the case of Christ” (Ruffin 1982, 145, 150). (One is

reminded of Therese Neumann, whose “nail wounds” shifted from round to

rectangular over time, presumably as she learned the true shape of

Roman nails [Nickell 2001, 278].) Moreover, Padre Pio lacked wounds on

the forehead (as from a crown of thorns [John 19:2]).

For years Pio wore fingerless gloves on his hands, perpetually

concealing his wounds (Ruffin 1982, 148). His supporters regard this

as an act of pious modesty. However, another interpretation is that

the concealment was a shrewd strategy that eliminated the need for him

to maintain his wounds. Before his death, frail, weary, with “rheumy

eyes seemingly fixed on another world,” Padre Pio celebrated Mass.

According to Ruffin (1982, 305), “For the first time in anyone’s

memory, he did not attempt to hide his hands at any point in the

service. To the amazement of everyone there, there was no trace of any

wound.” At his death on September 23, 1968, his skin was unblemished.

So, were Padre Pio’s phenomena genuine? Many other stigmatics—like

Magdalena de la Cruz in 1543—confessed to faking stigmata. Maria de la

Visitacion, the “holy nun of Lisbon,” was caught painting fake wounds

on her hands in 1587. Pope Pius IX himself privately branded as a

fraud Palma Maria Matarelli (1825–1888), insisting that “she has

befooled a whole crowd of pious and credulous souls.” Suspiciously,

under surveillance, Therese Neumann (1898– 1962) produced actual blood

flows only when the phenomenon was “hidden from observation.” And as

recently as 1984, stigmatic Gigliola Giorgini was convicted of fraud

by an Italian court (Wilson 1988, 26–27, 42, 53, 147).

Even a defender of Padre Pio’s stigmata, C. Bernard Ruffin (1982,

145), admits, “For every genuine stigmatic, whether holy or

hysterical, saintly or satanic, there are at least two whose wounds

are self-inflicted.” Catholic scholar Herbert Thurston (1952, 100)

found no acceptable case after St. Francis of Assisi. Thurston

believed the phenomenon was due to suggestion, but Padre Pio himself

responded to such theorizers: “Go out to the fields and look very

closely at a bull. Concentrate on him with all your might. Do this and

see if horns grow on your head!” (qtd. in Ruffin 1982, 150). As for

St. Francis, his extraordinary zeal to imitate Jesus may have led him

to engage in a pious deception (Nickell 2001, 276–283).

Canonization

Not only was Padre Pio accused of inducing his stigmata with acid,

he was also alleged to have misused funds and to have had sex with

female parishioners—in the confessional. The founder of the Catholic

university hospital in Rome branded Pio “an ignorant and

self-mutilating psychopath who exploited people’s credulity” (“Pio”

2008).

The faithful were undeterred, however, and after Pio’s death there

arose a popular movement to make him a saint. Pope John Paul II—whose

papacy sped up the process of canonization and proclaimed more saints

than any other in history (Grossman 2002)—heard the entreaties. Pio

was beatified in 1999. On June 16, 2002, he was canonized as Saint Pio

of Pietrelcina, but not before at least two statues of him wept in

anticipation. Unfortunately, the bloody tears on one turned out to

have been faked (a drug addict used a syringe to apply trickles of his

own blood), and a whitish film on one eye of the other was determined

to have been insect secretion (“Crying” 2002).

Interestingly, neither of the two proclaimed miracles of Pio (one

used for his beatification, the other for canonization) involved

stigmata. Instead, they were healings, assumed miraculous because they

were determined to be medically inexplicable. In short, the Church

never affirmed Pio’s stigmata as miraculous.

Of course, not everyone was happy with the canonization of Pio.

Historian Sergio Luzzatto wrote a critical biography of Pio called

The Other Christ. Luzzatto cited the testimony of a

pharmacist recorded in a document in the Vatican’s archive. Maria De

Viot wrote: “I was an admirer of Padre Pio and I met him for the first

time on 31 July 1919.” She revealed, “Padre Pio called me to him in

complete secrecy and telling me not to tell his fellow brothers, he

gave me personally an empty bottle, and asked if I would act as a

chauffeur to transport it back from Foggia to San Giovanni Rotondo

with four grams of pure carbolic acid” (Moore 2007). But if the acid

was for disinfecting syringes, as Pio had alleged to the pharmacist,

why the secrecy? And why did Pio need non-diluted acid?

Investigation shows the timing of this reported incident is

significant. The previous September, Pio and some of the other friars

at San Giovanni Rotondo were administering injections to boys who were

ill with influenza. Alcohol not being available, an exhausted doctor

left carbolic acid to be used for sterilizing needles and injection

sites, while neglecteing to tell the friars it had to be diluted. As a

result, Pio and another friar were left with “angry red spots” on

their hands. When Pio was subsequently alleged to have exhibited

stigmata, the other friar at first thought the wounds were from the

carbolic acid. Although Pio allegedly exhibited stigmata on his hands

as early as 1910, the “permanent” stigmata appeared, apparently, not

long after the carbolic-acid misuse (Ruffin 1982, 69–71, 138–143).

Sergio Luzzatto drew anger for publicizing the pharmacist’s

testimony. The Catholic Anti-Defamation League accused the historian

of “spreading anti-Catholic libels,” and the League’s president

sniffed, “We would like to remind Mr. Luzzatto that according to

Catholic doctrine, canonisation carries with it papal infallibility”

(Moore 2007).

Exhumation

Forty years after the death of Padre Pio in 1968, his remains were

exhumed from their crypt beneath a church in San Giovanni Rotondo. The

intention of church officials was to renew reverence and so boost a

flagging economy. Padre Pio, explained the Los Angeles Times,

is “big business” (Wilkinson 2008).

No doubt many anticipated that the saint’s body would be found

incorrupt. The superstitious believe that the absence of decay in a

corpse is miraculous and a sign of sanctity (Cruz 1977). In fact,

under favorable conditions even an unembalmed body can become

mummified. Dessication may result from interment in a dry tomb or

catycomb. Conversely, perpetually wet conditions may cause the body’s

fat to form a soaplike substance known as “grave wax”; subsequently,

the body may take on the leathery effect of mummification (Nickell

2001, 49).

Alas, Pio’s body, despite embalment (by injections of formalin),

was only in “fair condition.” So that it could be displayed, a London

wax museum was commissioned to fashion a lifelike silicon mask of Pio,

complete with his full beard and bushy eyebrows. The “cosmetically

enhanced corpse” went on display April 24, 2008, in a glass-and-marble

coffin (where it is to repose until the end of September 2009) “amid

weeping devotees and eager souvenir-hawkers” (Wilkinson 2008; “Pio”

2008). For those who wonder: no, there is no visible trace of

stigmata.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Herb Schapiro, who continues to send me useful

news clippings, and Tim Binga, director of CFI Libraries, for his

continued research assistance.

Notes

- For a discussion of fantasy proneness, see Nickell 2001, 84–85,

298–299.

- The three-inch side wound was seen relatively rarely and,

although “most witnesses” said it was cruciform, others described it

as being “a clean cut parallel to the ribs” (Ruffin 1982, 147).

Please help

the Padre Pio foundation .com. Please donate. Thank you.

Padre Pio and the

Padre Pio Foundation all Rights

Reserved.

|

|

|

|